The Book of Paying Attention and Its Relation to Performing Arts Projects

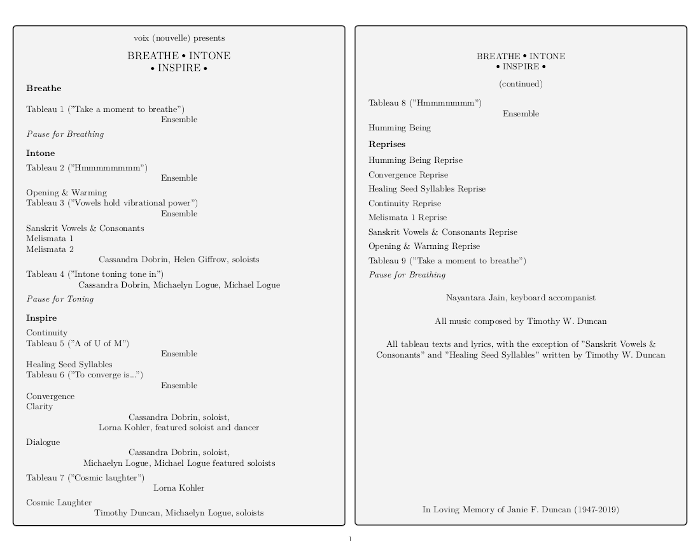

In 2019, I organized an enthusiastic group of local singers into an ensemble which I called voix (nouvelle). We gave two performances of a program entitled breathe · intone · inspire at two local venues.

_PCC_03-24-2019.png)

In 2021, I published on Kindle a collection of poems entitled The Book of Paying Attention.

Regarding the latter project I was asked the following rather provocative question:

How are you thinking of incorporating performing arts into your writings? Do you have an artistic vision yet of what you want to create?

The following paragraphs present a narrative account of how the two, i.e., writings and performing arts, have entwined throughout my professional career.

Vocal Work

I was active in school music and choirs throughout my elementary, middle and high school years. I joined the youth choir of Church St. UMC in Knoxville in my freshman or sophomore year, an affiliation that brought me into close and regular contact with renowned musicologist Calvin Bower. Prof. Bower was a fine organist and choral director. In addition to the use of highly imaginative use of instrumental (organ) improvisation during services, he integrated some of his own choral compositions into our weekly schedule of anthems. I found both the improvisation and his compositions to be very inspiring. As a beginning composer, I completed my first real composition after Prof. Bower left Knoxville, but organized a group of fellow singers and performed it in church from one of the balconies of this magnificent sanctuary at Church St. Church. I was either an high school senior or college freshman at the time.

I began vocal study at the age of fourteen with Prof. Edward Zambara, who would later rise to international prominence as a voice teacher and performance coach. I continued that study, not counting a “gap year” along the way, for ten years, culminating in a BM in Voice, which was an applied music discipline.

During my HS years, I came into increased contact with high quality poetry and drama. Later, while an undergraduate student, I began to compose music for performances of plays by Shakespeare, Marlowe and others, as well as conduct Gilbert & Sullivan operettas. In particular, I was invited to create original incidental music for a production of Marlowe’s Doctor Faustus. As part of that project, I worked with the lead actor and created a mix of his reading of the “Pact Scene.” At my request he read the scene four or five different ways, projecting contrasting emotional states and modulating his voice with equally diverse colors. Using the musique concrete methods of tape splicing and track bouncing, I created a sonic montage that interpreted the famous scene in rather innovative ways. The resulting mix was too “focal” to be used as part of the production, but I was encouraged to publish it some fashion.

Pact Scene from The Tragical History of Doctor Faustus by Christopher Marlowe

FAUSTUS. Then hear me read them.

[Reads] On these conditions following.

First, that Faustus may be a spirit in form and substance.

Secondly, that Mephistofilis shall be his servent, and at his command.

Thirdly, that Mephistofilis shall do for him, and bring him whatsoever he desires.

Fourthly, that he shall be in his chamber or house invisible.

Lastly, that he shall appear to the said John Faustus, at all times, in what form or shape soever he please.

I, John Faustus, of Wertenberg, Doctor, by these presents, do give both body and soul to Lucifer, Prince of the East, and his minister Mephistofilis; and furthermore grant unto them, that, twenty-four years being expired, the articles above-written inviolate, full power to fetch or carry the said John Faustus, body and soul, flesh, blood, or goods, into their habitation wheresoever.

By me, John Faustus.

Sound Texts

Composing for the theater (as well as a modest amount of choral and vocal composition) led to more serious study of composition at the masters level. All during that time my studies of poetry and drama grew and expanded. I also had the opportunity to analyze Gregorian chant and other examples of early liturgical music, not to mention composers such as Machaut, who was both the leading composer and the leading poet in France during his lifetime. These influences would begin to play out in unexpected ways in the future.

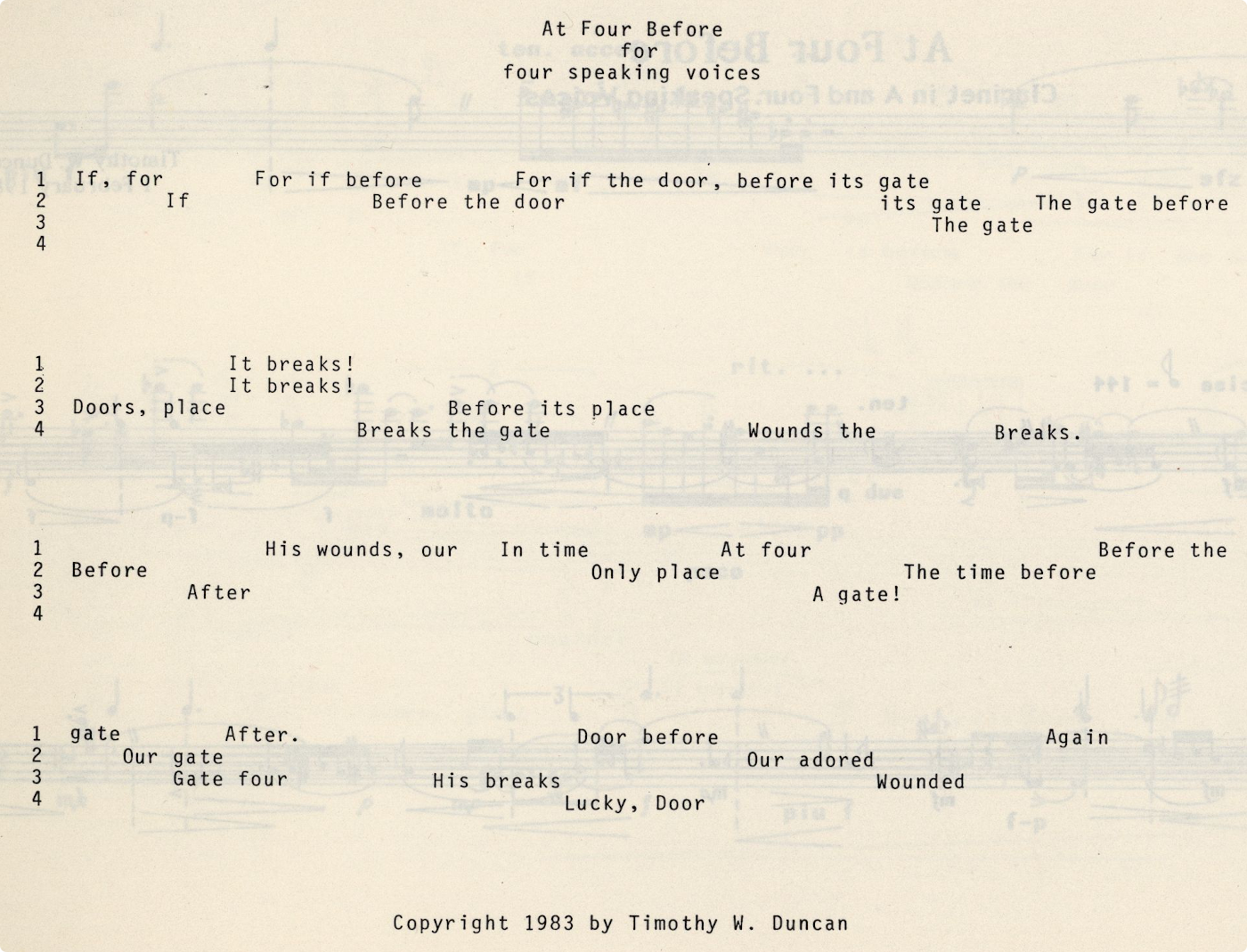

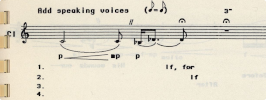

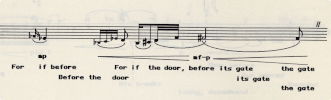

At Four Before

Between my masters and doctoral studies I was in Tallahassee, Florida, working as a technical assistant at the FSU library, while my wife attended grad school. I happened to be invited to a party of composers in which there was an expectation of bringing an original piece written for occasion. I had been studying Louis Zukofsky’s lengthy poem “A,” which has a section at the end that is “scored” for multiple readers and is accompanied by a keyboard part. Somehow this influence led to my writing an original poem for four readers for the composers’ party, entitled “At Four Before.” Ultimately, the poem found a home in the middle section of a piece for solo clarinet. However, I brought it to the composers’ gathering where we divided up into sections and read the work as a choral poem. It was quite well received. “At Four Before” demonstrates an interest that I have maintained throughout my career in creating and reciting texts that involve multiple voices and in which the sentence structure is “atomized,” in other words, the narrative flow is distributed among several speaking parts. This tendency will manifest in subsequent projects as well.

BTW, at least one listener has tried to connect this poem with certain well-known Christian imagery. I don’t believe that this is the case. My thinking at the time that the scene depicted here was that of a rather common place domestic accident.

Profond Miroir

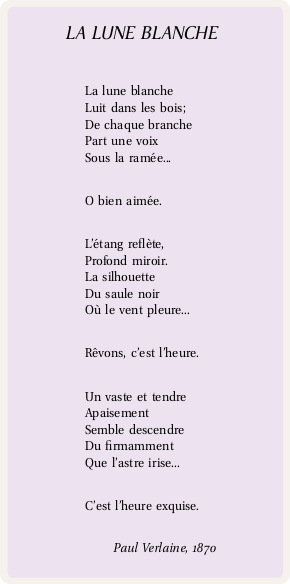

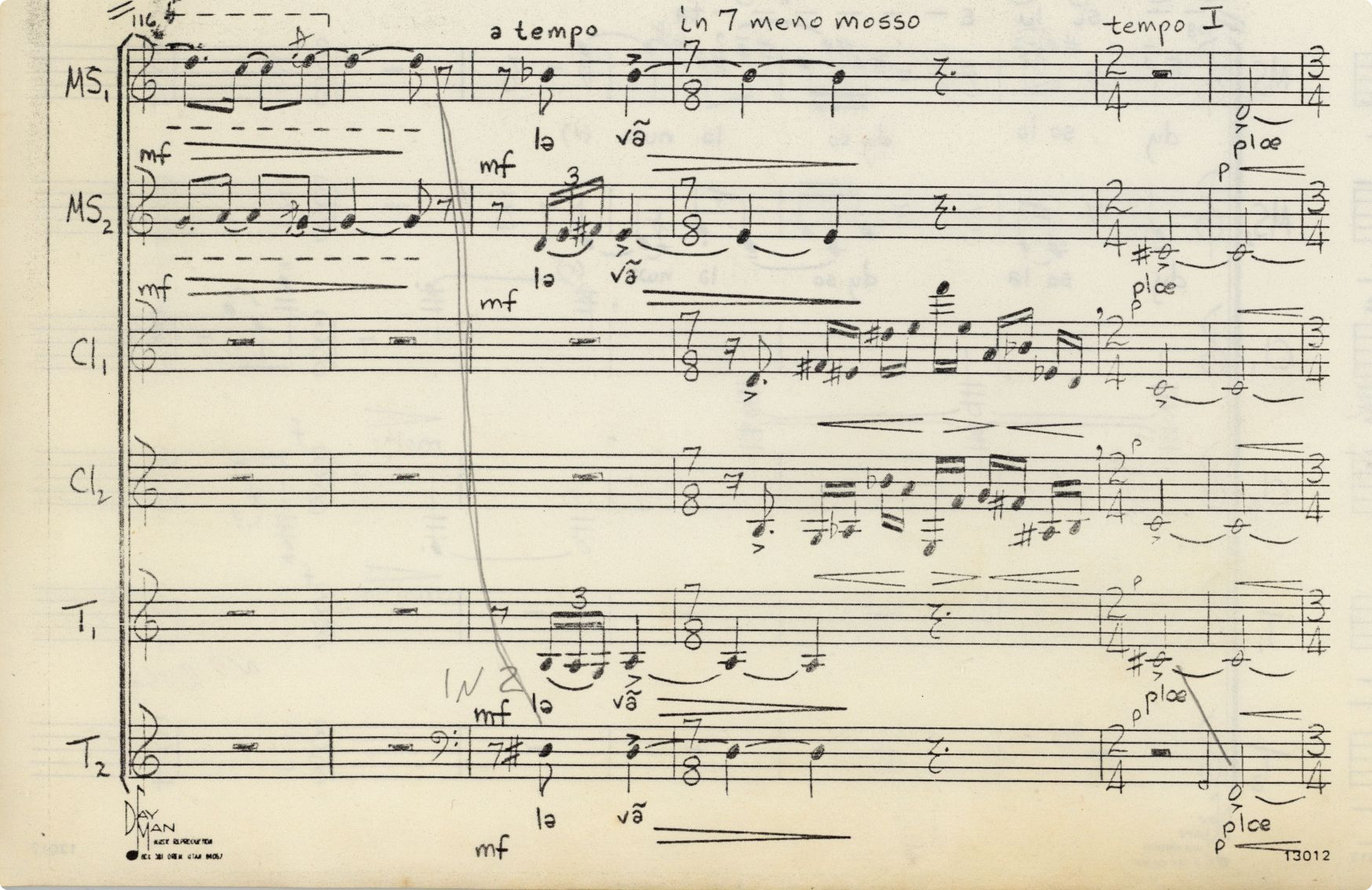

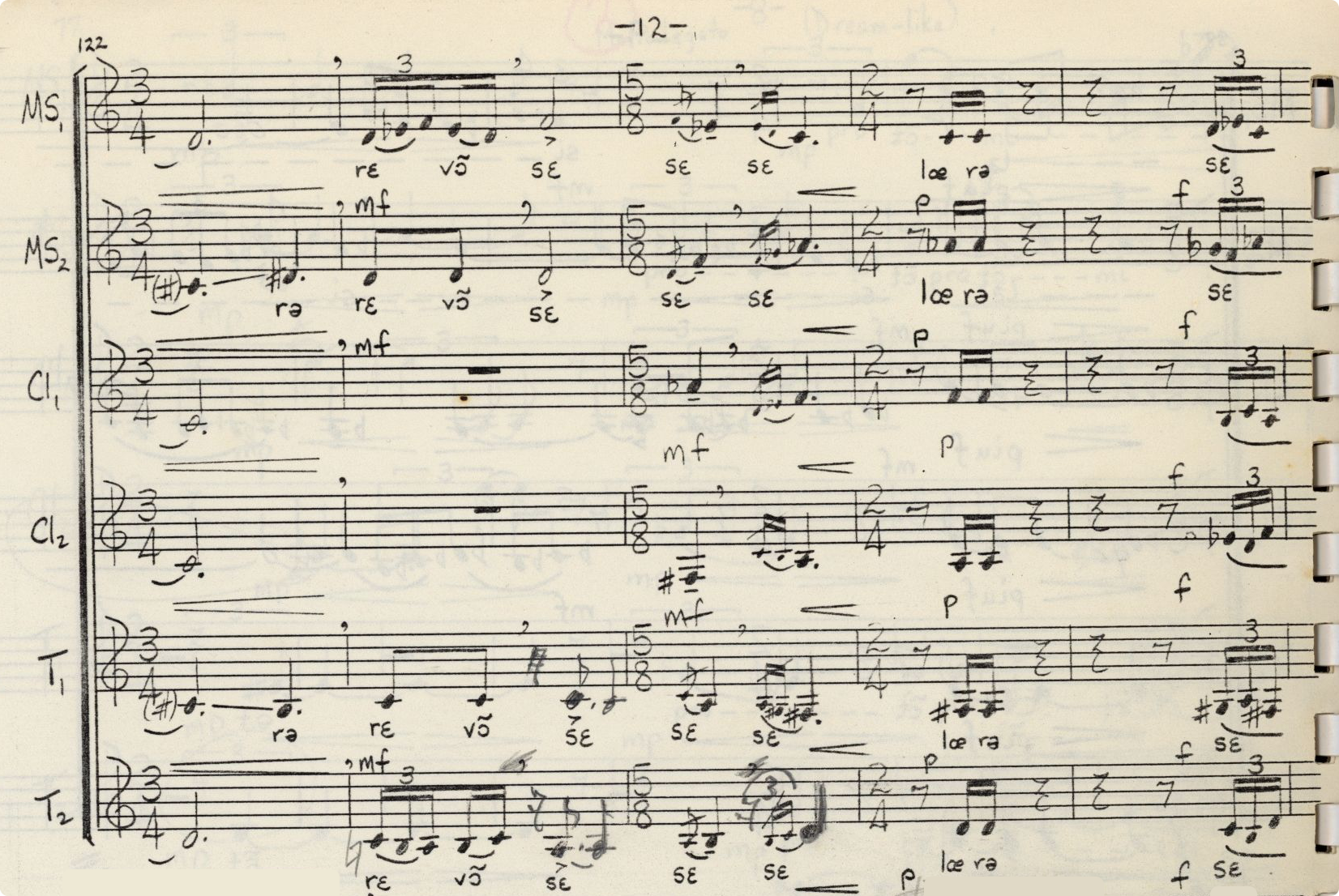

At the UC College-Conservatory of Music I had the privilege of studying with composer and theorist Jonathan Kramer. Prof. Kramer was working on his landmark study The Time of Music: New Meanings, New Temporalities. I had during this period the advantage of both theory and composition study in the presence of someone with an extraordinarily expanded mindset. I composed an ensemble piece for two mezzo-sopranos, two clarinets and two tenors based on Paul Verlaine’s symbolist poem La lune blanche. The composition musically exploited the technique of mirror inversion, with the two mezzo-sopranos and one clarinet being mirrored by the two tenors and the other clarinet. The musical structure was over 12 minutes long and the 80+ syllables of the poem stretched over the structure through the simple operation of arithmetic division. This resulted in melismas along with vertical and temporal juxtapositions that probably created the perceived effect of the textual meaning fading in and out. One other feature is that the text was printed in International Phonetic Alphabet, as a strategy for distancing the singers from the literal meaning of the poem. Interestingly, listeners reported to me after the performances that there were places in which the text setting powerfully evoked the the luminous imagery of the poem.

Profond Miroir (excerpt)

Curves of Things Through Time

During the years of my first full-time teaching position (i.e., in Mississippi) I composed two complete programs of original work. One was in collaboration with a modern dance company. We toured a number cities throughout the South under the name Curves of Things Through Time. One piece, entitled …and then we dreamt of clear water until breakfast, was mostly a synthesized composition with some live and recorded solo vocals (me) at the very end. I sat cross-legged on a rug with a microphone in a meditative poise while the piece largely played out on its own. The music was quiet, spacious and dreamy. I had no idea that I would revisit the gestalt (if not the sonic colors) of this performance many years later in a program entitled breathe · intone · inspire.

…and then we dreamt of clear water until breakfast (excerpt)

Star Concert

The other program of original music from this time period was a choral concert accompanied by synthesized music. One of our concert venues was the Russell Planetarium in Jackson, MS. The texts were biblical and the confluence of performance in a planetarium (with slides on loan from NASA), the use of synthesizers, and the setting of imagery that often invoked celestial objects, was deliberate. In this one excerpt, from “Lift Up Your Eyes,” there is a place where the womens’ voices repeat a section of text ad libitum under the sound of a men’s chorus and synthesizer solo.

Lift Up Your Eyes (excerpt)

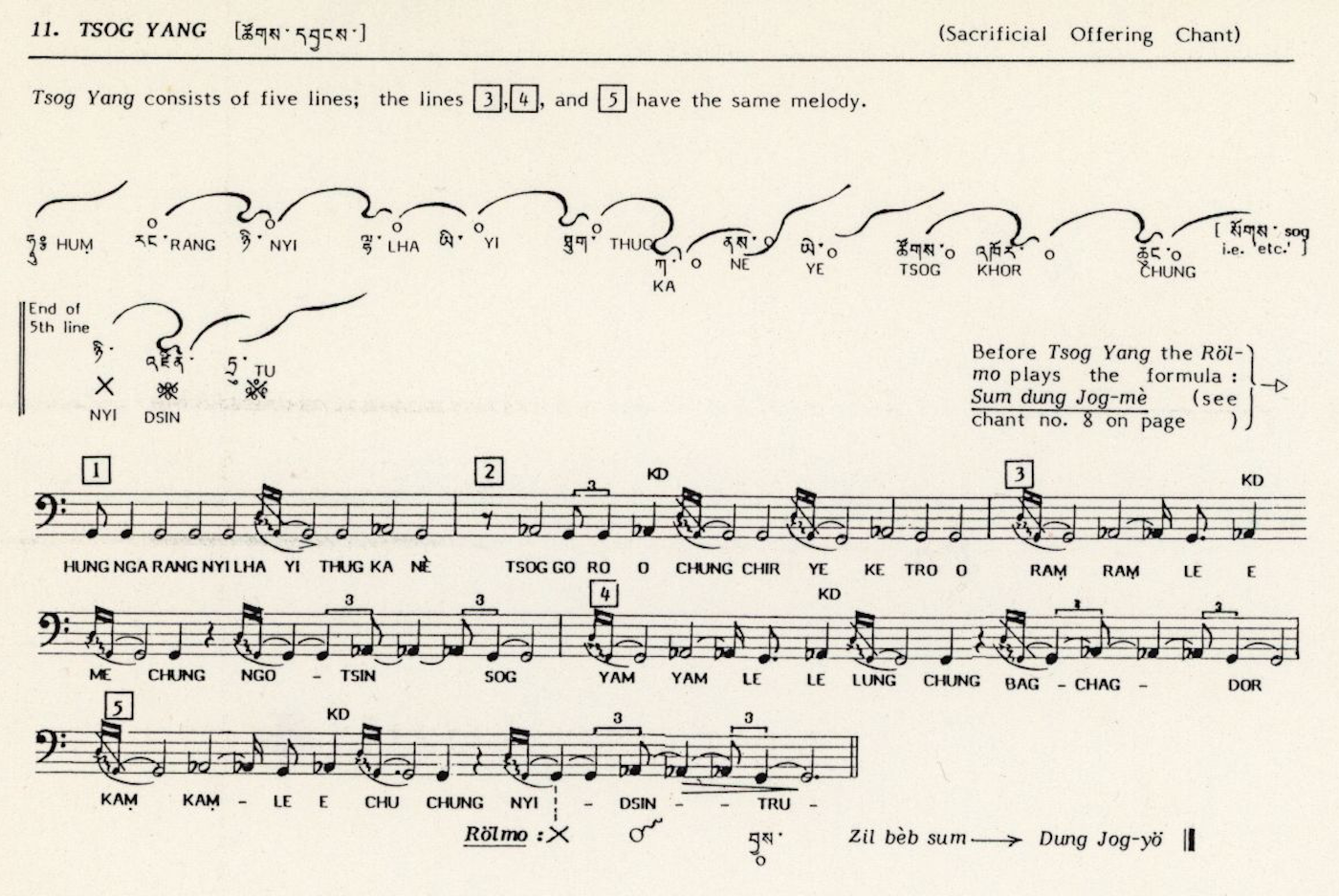

Tibetan Chant in the Nyingmapa Tradition

In 1992 I moved to the Santa Cruz Mountains to live and study at a Tibetan Buddhist meditation center. There I encountered the practice of sadhana with its traditions of chant, utilization of mantras and visualization practices. There was also the opportunity for me to participate in Cham, the ceremonial dance presentation that occurred two or three times a year.

While the multi-phonic style of certain Gelugpa monasteries is well-known in the West, the older style of Nyingmapa chant was a real revelation. There are places in long sadhanas in which the Umdze (chant master) seems to improvise melismas while adding syllables to dilate the moment and direct essential emphasis to the visualization. Ethnomusicologist Daniel Scheidegger transcribed a number of these Yang (i.e., melodic) passages into Western music notation (example above). He conducted his research primarily in Nepal in the 1980s. By fortuitous connection, I was able to study with the same Lama in California that instructed Dr. Scheidegger in Nepal.

Artistic Action and Mindfulness

In 2004 I gave a 90-minute solo presentation at the IdeaFestival in Louisville, KY entitled Artistic Action and Mindfulness. In the notes (really, a long essay) that I prepared for that presentation I wrote:

The intersection of art and energy in much traditional and modern Asian art suggests a transfer from one state to another, much in the same way we can think of light sometimes in the form of waves, other times in the form of particles. They certainly complement each other. Mindfulness traditions use music, dance and visual art as a way of letting the effects of mindfulness in. Art can clearly produce threshold experiences. Non-art/anti-art can provide moments of clarity and lucidity. Someone once said that the real yogis of the West are its artists. At the same time, because art is art and not philosophy, the cultivation of these experiences often lack a contextualizing framework, which might be one powerful reason that so many Western artists have turned to Asian mindfulness systems as a part of their way of life.

I would say now that The Book of Paying Attention is intended to provide such a contextualising framework.

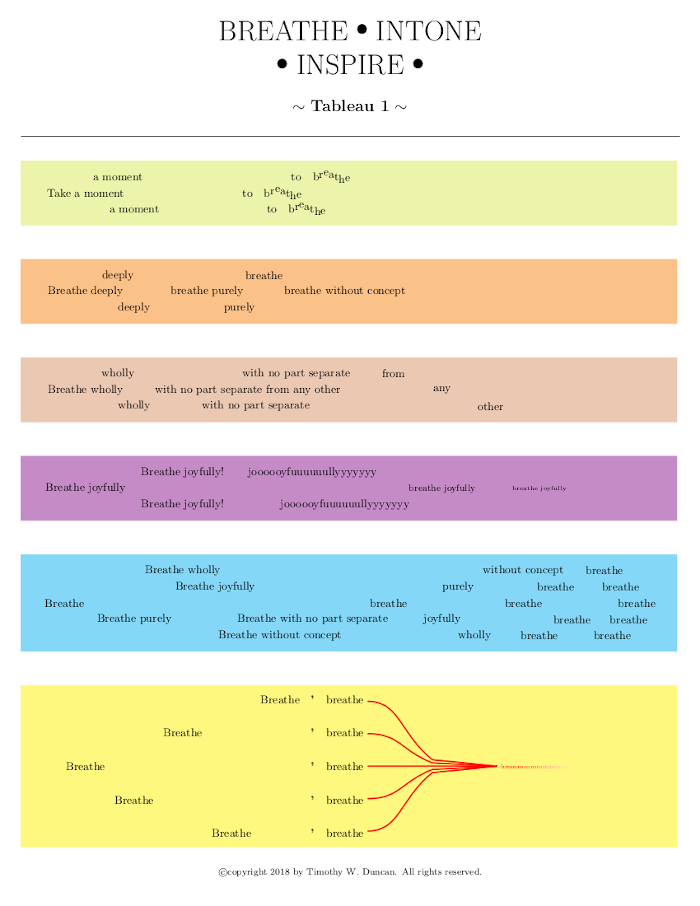

breathe · intone · inspire

_PCC_03-24-2019.png)

The program breathe · intone · inspire consisted of both sung pieces and eight poetic texts that were spoken in ensemble, much in the same same manner as At Four Before. The program as a whole was organized as a flow sequence, with a certain amount of movement, as well as a centerpiece of audience participation. The program was conceived as a departure from either narrative or poetic sentiment and an attempt to create an experiential space using vocally induced vibration. John Cage once wrote,

I determined to give up composition unless I could find a better reason for doing it than communication. I found this answer from Gira Sarabhai, an Indian singer and tabla player: The purpose of music is to sober and quiet the mind, thus making it susceptible to divine influences.

This motivation helps to position the purpose of breathe · intone · inspire very precisely. In the program booklet to accompany the performance I noted:

What is conjectural is the extent to which the recitation of of pure vowel sounds, such as AH, when singers vocalize in the Western classical tradition, or phrases of syllables - possibly without literal meaning - carry sufficient vibrational impact to bring about transformational results. A renowned researcher in the Twentieth Century, Dr. Alfred Tomatis, once wrote, If your voice has good timbre, is rich in overtones, you are charging yourself each time you use it, and of course you are providing a benefit to whomever hears you! To put this concept into practice, along with other related transformational techniques involving voice, such as humming, form the basis of breathe · intone · inspire.

The Book of Paying Attention

I see breathe · intone · inspire as a prototype or template for further exploration. Indeed, there are still presentational aspects to the music (in particular) of this program that can be more closely integrated with speech, movement and audience interaction, as well as some use of improvisation. The concept would still be that of a flow, an energetic experience occasioned by vocal induction of auditory vibration, modulated in various ways by spatial factors, vowel colors, pitch and rhythm contours (often in non-traditional ways), and the absence of explicit narrative or poetic sentiment. The Book of Paying Attention contextualizes the value of awareness in the moment. The program breathe · intone · inspire and its successors are intended to open experiential space and recognition of the moment.

It is worth pointing out that the last page of the main text of The Book of Paying Attention ends with an incantation of sorts, what one of the early reviewers of the book described as…

…the last portion of the piece with the different vowel sounds, consonants and expression which really lifts you into the stratosphere!

Returning to the question posed at the beginning of this essay,

How are you thinking of incorporating performing arts into your writings?

I find that both my writing and my performance arts activties are driven by the same aesthetic and spiritual concerns.

\(\triangleleft\) Essays